Arnold Levin, Workplace Strategist at SmithGroup, urges the workplace design community to focus on external disruptions and begin to engage in organizational and process changes.

An Odd Title for an Article on Workplace Design

An odd and perplexing title for an article on workplace design, but one that I believe helps define the current and future business landscape in which we as workplace designers and strategists find ourselves. As many of you may remember, Chicken Little was always going around bemoaning and warning of impending doom and because it never happened, at least not until the end, he was ignored, and a potentially perilous situation occurred.

Deviance Theory is the sociological equivalent of Chicken Little’s tale. The theory is based on the notion that predictable disasters are often ignored due to group thinking and culture. The longer these predictable disasters or disruptions do not occur, the more one becomes desensitized to its ever-present danger. When this occurs and creating solutions isn’t prioritized, the deviance becomes the norm and the predictable disasters eventually occur. Strong project managers use Deviance Theory to uncover potential or impending problems in construction and project management systems. The classic case of Deviance Theory was chronicled by Diane Vaughan, a professor of sociology at the University of Chicago, in her book “The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA“. Professor Vaughan outlines how the Challenger disaster was predictable. She examines the very real possibility that the O Ring failure (the shuttle’s component that resulted in the fatal explosion) along with its catastrophic implications, was known to the NASA engineers and their consulting engineers. The culture at NASA referenced in the title refers to an organizational environment that existed where dangers were known, but because the longer-term consequences did not develop, a false sense of safety continued, ultimately leading to a horrendous disaster that could have been avoided if a different culture existed.

As a profession, we develop workplace strategies and design solutions to help our clients face the unpredictable challenges and disruptions within their industries. However, we fail to see or acknowledge those very same disruptions in our own industry. Subsequently, we continue business models that face the same risks and need for change as our clients’ industries. Every time a recession hits and impacts design organizations, conversations increase around the need for different business models to ward off the disastrous repercussions of staff layoffs in the future. The economy returns to some semblance of normalcy, and we fall back within our comfort zones, thereby avoiding the difficulties of change.

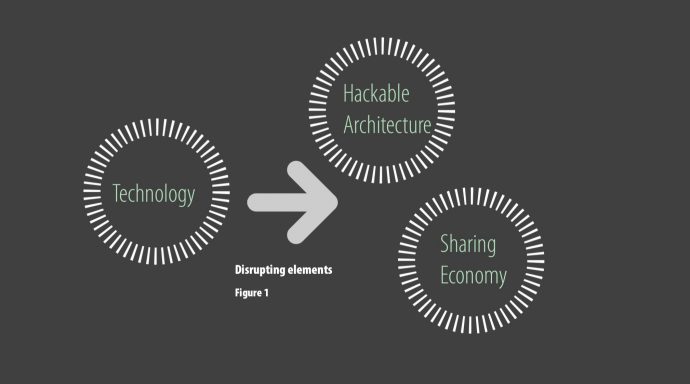

Of more concern to the profession than the results from continued economic downturns is the impending industry disruptions. These disruptions result from the very same forces that are disrupting our clients’ industries, mostly centered on the sharing economy and technology. One key example is the automobile industry. Formerly positioned as manufacturing companies, now they view themselves as mobility organizations – moving from a model of manufacturing to one of technology. Likewise, financial institutions find their services gradually eroding to technology companies, from start-ups to Apple and Amazon. Change is imperative for our clients, but like Chicken Little, a culture of deviance exists within the design profession (including both the furniture and real estate industries’ supporting the design enterprise). The longer we ignore these disruptors, the more likely we’ll be pushed out of the equation completely.

The Past: When Architects and Designers Ruled

This is not the first time that our industry has been faced with changes, though the challenges discussed here have far greater consequences than those of previous disruptions. I am old enough to remember a time when our profession was all encompassing in terms of the services we provided and compensation. We offered a range of services that included not only programming but process analysis, design, design documentation and project management that went beyond managing our design teams. Our profession failed to successfully manage the project delivery process, and more importantly, we failed to make the business case to our clients that we were more than capable of doing so. Because of this, the project management industry was born, thereby eliminating a once important role of the design consultant. We completely ignored the danger which resulted in a diminished role of engagement with our clients.

At that time, the design consultant orchestrated the entire process, from design to furniture procurement. Competition was limited to other design firms, not other industries. Due to these ‘other industries’ being more astute as to potential business opportunities, as well as threats within their own industries, both furniture manufacturers and real estate consultants started offering services that competed with designers, primarily in the workplace strategy arena. The competitive field dramatically expanded and become more ambiguous.

In 1997 while pursing my MBA, I was assigned within my marketing module to research a threat to an industry and offer potential strategies to overcome those threats. I chose the design profession as my market. My research paper disclosed how the greatest threat to design and architectural firms (remember this was 1997) was not other design and architecture firms, but furniture manufacturers and real estate consultancies. This was before these two industries entered the field of workplace strategy. I based my conclusions on the fact that these two enterprises had the economic capacity to engage in meaningful research that was practically void in our industry, thereby providing an advantage around thought leadership. They also had the capacity to invest in talent and collateral materials, and the potential to engage with organizations both before architectural and design firms could, and in some instances, get to the coveted C-suite.

SmithGroup recently pursued workplace and real estate strategy services for a large advocacy organization headquartered in New York. Half of the competition was comprised of traditional architectural workplace organizations. The other half were service and experiential design firms who did not have a portfolio of built workplace environments. It was one of these organizations that ultimately secured the project.

Our response as an industry to these external advances and market competition has traditionally been to continue on the same path, offer similar workplace strategy services, not impactfully differentiate ourselves, and utilize the same business model as in the past. The sky is falling!

Disruption Part 1: Them

Much has been written over the last several years on the sharing economy and its impact on many organizational enterprises. The sharing economy fueled by technology and the breaking down of siloes across once individual and internally focused industries, along with the belief in sharing information and resources, has created new and innovative businesses and eliminated a greater amount of businesses. From Uber disrupting the taxi business, Amazon the retail industry, Apple the music and computer industry, disruption is everywhere, and no industry or profession is immune. These disruptions are not just eliminating once solid organizations, they are reshaping what and how those industries are structured and designed as business entities.

Ford and General Motors are now in the technology and mobility business. IBM, once the leader of the computer world, is now a technology consultancy, preaching the importance of design thinking. Amazon recently announced their involvement in the healthcare industry along with J.P. Morgan and Berkshire Hathaway. It will not be long before these organizations impact the delivery of healthcare as well as the architecture and workplaces where healthcare is delivered. One of the questions I pose to clients when we engage with them in trying to understand the consequences of potential disruptions to their business, is “what would happen if Google entered your industry? What would the impact be in your business model and subsequently in your workplace needs and responses?” This totally changes the narrative and thinking around future proofing the workplace.

Nowhere has disruption been evidenced more in terms of workplace design than with co-working. Both as a physical entity, as well as service entity, it has influenced not just the functional mannerisms of how we design workplaces but the visual imagery around those workplace design solutions. It has resulted in the blurring the lines between work, retail and hospitality. Co-working is viewed as the great disruptor of work and place. Somewhere Starbucks has been forgotten and not given its due. Without Starbucks, and the ability to work amidst the noise and ambience of a dark coffee house, there would probably be no co-working.

But as little we, the design community, responds to these disruptions, we provide multiple image solutions and discuss with our clients how their workplace needs to be more like a co-working establishment. While grounded in part to the very real changes in organizational needs, flexibility and adaptability as well as real estate costs, our embracing of this disruption for our clients allows us to still miss the disruptions to our industry. This response only touches the surface of the impending problem. We have moved from Chicken Little to Deviance Theory.

Disruption Part 2: It’s Not Just for Them

Let’s now explore how these very same disruptors to our clients’ organizations have greater ability to influence and disrupt our industry along with ancillary industries such as furniture and real estate. Three of these disruptors are WeWork, Convene and hackable architecture.

WeWork is no longer targeting the small startup organizations waiting for investors so they can then move on to larger facilities. IBM along with other large corporate entities are leasing thousands of square feet of WeWork space. In that same pursuit I referenced earlier, the client requested the responders to address when and what would trigger them to include co-working spaces as part of their real estate strategy. Adoption of co-working is now mainstream to many conventional business organizations. This thinking is not limited to corporate workplace entities. A recent conversation with a large national health care provider focused on their consideration of leasing co-working space as part of their future real estate strategies.

Convene partners with commercial office developers to provide the space typologies one would associate with co-working spaces, converting the conventional office building into a form of co-working. The culture around the shared economy allows this to become the new paradigm and the new expectation. The business model is also based on the founders’ theory that lease durations will continue to get shorter (from a onetime average of 10 years to five and ultimately, according to their research, one year). With a one-year lease, tenants will not get the build out allowance they have in the past. This will prevent companies from building individual amenity spaces (large meeting rooms, cafés, fitness centers, etc.). The multi-tenant office building transforms into a co-working opportunity that provides these all too expensive space typologies. In addition, one can interact with fellow tenants rather than be isolated and siloed within their own organization.

Hackable architecture is the result of both the shared economy and the proliferation of 3D-printing capabilities, increasingly at affordable cost points. Carlo Ratti, head of MIT’s Media Lab and an architect, outlines in his two books, The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life and Open Source Architecture, the notion that the culture around the shared economy is driving greater demand on potential clients’ ability to actively participate in the design of their facilities as well as to own the process. He foresees that they will become a more active stakeholder in the design process. This, along with accessible use of 3D printing, will allow individuals and organizations to both design and construct their own spaces.

The impact of these three disrupting elements has the potential to change not only the design industry but the furniture and real estate industries as well. Taken from the vantage point of Chicken Little, not only will co-working influence the approach to workplace design from the design profession, but also the furniture manufacturers and real estate consultants. If mainstream organizations increasingly gravitate to this form of real estate strategy, it represents a potentially large number of organizations that will no longer need the traditional services of architects and designers. WeWork has their own workplace strategy and design teams. With organizations being comfortable with the aesthetics and strategies associated with co-working, they will no longer need the conventional services of design organizations. Co-working spaces offer built out environments that have the same appeal to organizations as do the custom designed spaces the workplace design profession provides. The added benefit resides in not having to wait on construction times as well as having the flexibility to expand or contract to respond to an increasingly uncertain business environment. Flexibility! It’s a built-in component and one which the design profession has been late at adopting in its approach to workplace design strategies and solutions.

Further, if these organizations are equally if not more comfortable with the furniture opportunities provided within co-working enterprises, this will impact the sales of the traditional sources of designer-focused furniture. And the real estate industry is not exempt (in case you were wondering). With WeWork positioning itself as being the largest provider of real estate both in tangible products and services, there will be a dwindling market for leasing commercial office space. Added to this scenario, is the impact of Convene and similar organizations, who view real estate as a service, not as a tangible asset. With shorter leases, and subsequently smaller build out allowances, the types of spaces that are coveted by designers to create exciting workplace designs, will become part of the commercial office building in the form of shared amenities. And they too (Convene) have their own strategy and design component. A potentially serious disruption to the design and furniture industry. And again, not to leave out real estate consultants, one-year leases do not incur as high a fee as a five or ten-year deal.

Some who are not fans of Chicken Little, or do not accept Deviance Theory might dismiss my thesis as too far off or extremely uncertain. I would suggest that this form of thinking is at the very core of Deviance Theory. As Carlo Ratti points out in The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life, architects (and designers) need to change their business model from one that relies on design as the built product, to one that is formed around and focuses on design as a service. Other design organizations have made this business model shift years ago. IDEO is an excellent example of a design enterprise that moved from a traditional industrial design consultancy focusing on physical tangible products (think OXO) to a design service provider, engaging in solving business, service and organizational problems, whose ‘design’ solutions transcend the physical. The workplace design profession (rather than comforting themselves in a rather prosperous economic climate, putting off investing in substantive changes to their business model) needs to focus on the external disruptions that are looming over our business model and begin to engage in the organizational and process changes that should have been started decades ago.