Steve Gale, Workplace Strategist at M Moser Associates, explores the current state of change management in the workplace industry.

Change management is usually touted as a specialist discipline, but for workplace designers, it comes with the territory. Designers are all change managers, whether they like it or not, especially in the post-Covid era when uncertainty is rife.

Think for a second about what designers do for a living. They take the vessel that contains the crown jewels of an organisation (the people and their kit), empty it, make a new one, and pour the people back in, often in a different location and configuration. Most of the time, this is a risky, contentious, and disruptive exercise. Each workplace project delivers substantial changes, and the design team usually has to manage the impact. This is not a new phenomenon.

A project’s biggest challenge is rarely technical. We are comfortable with the physical stuff; it is much more likely to come from people. Buildings, being inert, do exactly what designers ask of them, but people do not. Our clients and their employees deserve all the help they can get to adapt to their new space. If their voice is not heard and responded to, projects can be at risk.

The training and experience of designers does not usually qualify them as natural change managers. Still by collaborating with workplace strategists internally, engaging with the client team and deeply understanding the importance of psychological buy-in, they succeed despite the lack of formal education.

We cannot adapt the internal wiring of every designer, nor would most clients want to hire change managers for every project. So, let’s help by repackaging the problem and making it simpler, as designers are already doing most of it anyway.

Our industry usually has to function with a slimmed-down version of the change management inputs needed for critical corporate transformations. Designers can filter out the unnecessary bits and use the principles that are left. Here are a handful to start with.

Why Change?

Everyone in the project team must be able to answer this simple question. The client’s reasons should be clear, consistently expressed, and easily understood by all those affected. This does not mean that they will be universally accepted. The business drivers for change should resonate through the design decisions.

Honesty is essential and avoids the risk of treating employees like fools – which they never are. Often, cost savings are sold as increased flexibility or promoting greater interaction. Employees understand cost control as a necessary business objective, but they might want the chance to ask what is in it for them. Credibility is paramount when explaining why changes are a good thing.

Different Speeds of Change

We frequently hear that “people don’t like change,” but that is not really fair or accurate. People can accept huge transformations, but they eat them up at a certain rate. It is worth considering what that rate might be, and then working with it.

A simple example is when occupants move office, the change in their surroundings and routines is not gradual. It is a step change, perceived in an instant. They go home on Friday night with a new address for Monday when their new world starts at 9 o’clock –almost instantaneous in terms of working hours.

We frequently hear that “people don’t like change,” but that is not really fair or accurate.

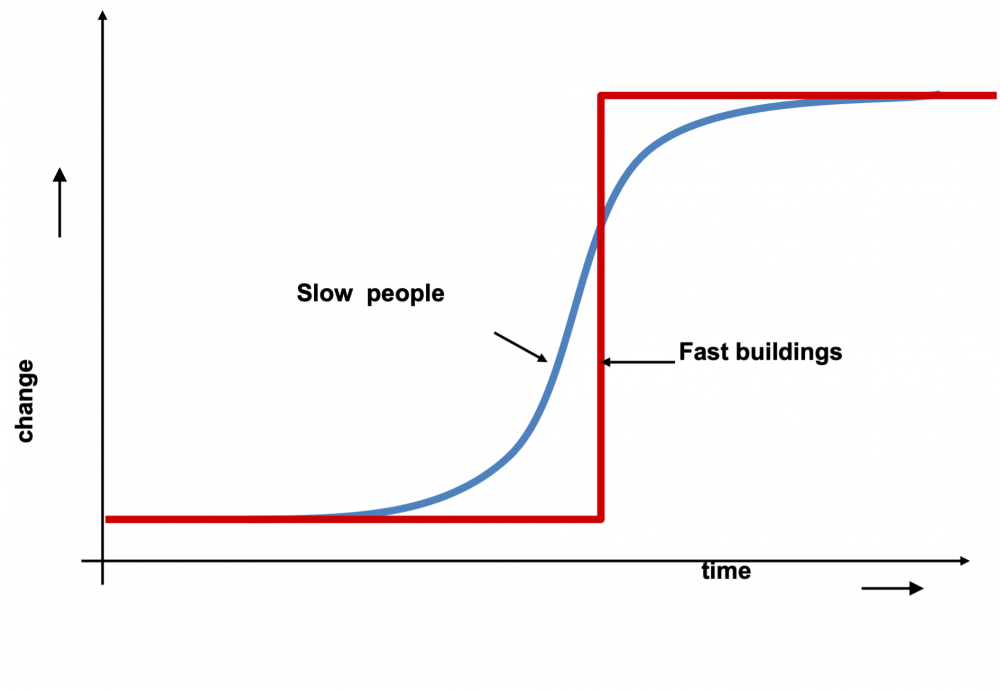

People, however, do not change this fast. They change slowly, in tiny increments, if at all. The chart below compares the light speed change of buildings to the glacial speed of people. If you impose a new environment before the occupants are ready to accept it, you will have to deal with their pain while they get used to it, if indeed they ever do. People are brittle, and they have a lot of inertia. When they move, they take a while to get going, and when they bend, it is creakingly slow.

Risk Assessment

A project team must quickly estimate how ready the occupiers are to embrace any proposed changes, which probably means conversations with a wide range of people. An assessment should try to understand whether adoption might be achieved by education, or by repositioning deeper emotional and cultural values.

For example, novel space booking procedures might need training, but turfing senior people out of their caves might offend deeply held ideas of their worth, or even identity. These two examples are not equally risky.

Knowing When to Stop

Crucial to any assessment of readiness is understanding when a change might be a bridge too far. There are times when a change does not look like it will be adopted in the time allotted, so the project team can decide to engage more resources, buy more time, or reduce the scope to make it more palatable and feasible. A minor success is better than a big failure.

Rejection and Resistance

If a project encounters neither of these, your job will be easy, but the sooner push-back can be identified, the better. One of the hardest jobs is to persuade business strategists that their initiatives might not go down well with employees. Their expectations need managing just as much as the occupiers. Balancing leadership expectations with employees is a vital diplomatic task and will determine the trajectory and speed of adoption. Dealing with resistance is often the most challenging task, as coordinated resistance can derail a project or place extremely high costs on its delivery.

Poorly managed projects can make people work inefficiently for extended periods, leave the business altogether, or conspire to reverse the changes, which can be bruising for all sides and wastes a lot of money.

Communication

Communication is at the centre of all change models, and it is tempting to imagine that really good communication can resolve everything. We can hope that people will buy into a project’s aims if they are educated and informed, and that agreement will come with understanding. Neither are guaranteed.

The crucial discipline of communication is its own subject area covering things like channels, content, timing, and voice. Communications often needs separate specialist input from a client-side expert, but for the design team there are two big issues.

…Communication is a two-way street, not just a show and tell.

The first is that communication is a two-way street, not just a show and tell. Unheard voices will store up problems for later, when they will be much more difficult to deal with. Your hearing is at least as important as your voice.

The second is the fear of over-communication and the risk of dilution. Experience shows that occupants rarely raise this, but the opposite is a frequent complaint. It is safer to err on the side of more, not less.

There is no limit to the complexity of change management, but a good design team can carry it as part of the delivery process using their experience, empathy, and humility. This will be especially critical following the pandemic as working patterns evolve into a new normal.