FCA’s Steven Stainbrook explains why it is time to return to the corporate campus—not the office.

Endless articles have been written on the ‘return to work’ suggesting every fathomable solution with the hopes of making in-person engagement meaningful for offices across the country. Designers have imagined a jungle gym of installations to support everything from a treehouse for solitude to a carnival tent for collaboration. Workplace strategists have sought to segment personas in an attempt to optimize operations for every conceivable employee behavior. It is only out of professional exhaustion that I agreed to share my perspective and suggest that the industry is desperately attempting to artificially intellectualize office design in hopes of gaining new clients, a short-lived marketing splash, or perhaps to preserve what is left of yesteryear’s commercial office market. Let’s posit, for the purposes of this piece, that the world’s major corporations believe the hybrid workplace is here to stay and most are actively considering reducing their physical footprints.

After a two-and-a-half-year at-home routine, the general office population is not returning to a pre-pandemic setting and the data supports this:

- Some global corporate clients are assuming a maximum occupancy of 65% on any given day

- Kastle security pass card data shows the country’s largest cities averaging a return rate in the 30 percentiles

- Record high lease concessions (growing 27.7% nationally over 24 months) parallel falling listing rates suggesting demand remains muted (Avison Young)

- Lease term durations declined 12.6% indicating a lack of confidence in pre-pandemic workplaces

- Avison Young’s proprietary “AVANT Vitality Index” is at 41.9% for weekday foot traffic in office buildings

It should be no surprise that given the opportunity to revolt against the financially driven open office model, people have solidified their abhorrence of benching systems. The corporate design industry embraced space-saving measures and coined it collaboration. The pendulum will swing back to some semblance of responding to workers’ needs and provide spaces to do what people need to do in an office—have meetings, share ideas, organize teams, and provide spaces for people to focus. In the spirit of responding to how people work we should remember that 76% of Americans still drive to the office (Statista’s Global Consumer Survey). Perhaps the A&E industry should turn their attention to the once deemed passé corporate campus. It is time to return to the corporate campus—not the office.

It is time to return to the corporate campus—not the office.

The same data suggesting the decline of the office includes a curious exception with the Sunbelt markets leading in demand with positive absorption over the past four quarters. Included in this vast region is Austin, Texas, with office occupancy (in-person) rates of nearly 60%. Another outlier in our real estate ecosystem is the relocation of remote work households to areas with a better quality of life and greater sense of housing choice. This migration has elevated smaller and more affordable markets to the top of the Emerging Housing Markets Index in the second quarter of 2022. Subsequently, the top 20 cities in the ranking have an average population size of about 400,000. Both the Sunbelt and smaller cities share commonalities such as being readily accessible to outdoor recreational activity, overall affordability, lower unemployment rates, appealing lifestyle amenities, and greater ease of personal transport—in short, a mixed-use corporate campus. Campuses are inherently closer to a dispersed workforce, outside of large metropolitan areas, and are poised to come roaring back.

From the ‘great resignation’ to the ‘great repurposing’ office parks and corporate campuses could offer a panacea to today’s workplace conundrum.

From the ‘great resignation’ to the ‘great repurposing’ office parks and corporate campuses could offer a panacea to today’s workplace conundrum. This solution is holistic in nature and is a wise step beyond the biophilic design craze. One of the benefits of working from home is the ability to change your scenery, step outdoors, take a call from a patio, or a reprieve in a garden. Campuses can offer similar characteristics of the Emerging Markets Index—easy to come and go, walkable environments with access to recreation, food, and other amenities. Lest all lessons learned from urbanism be lost, attention should be given to the principles of great public space. Exurban campuses can be reborn into vibrant destinations for work and play.

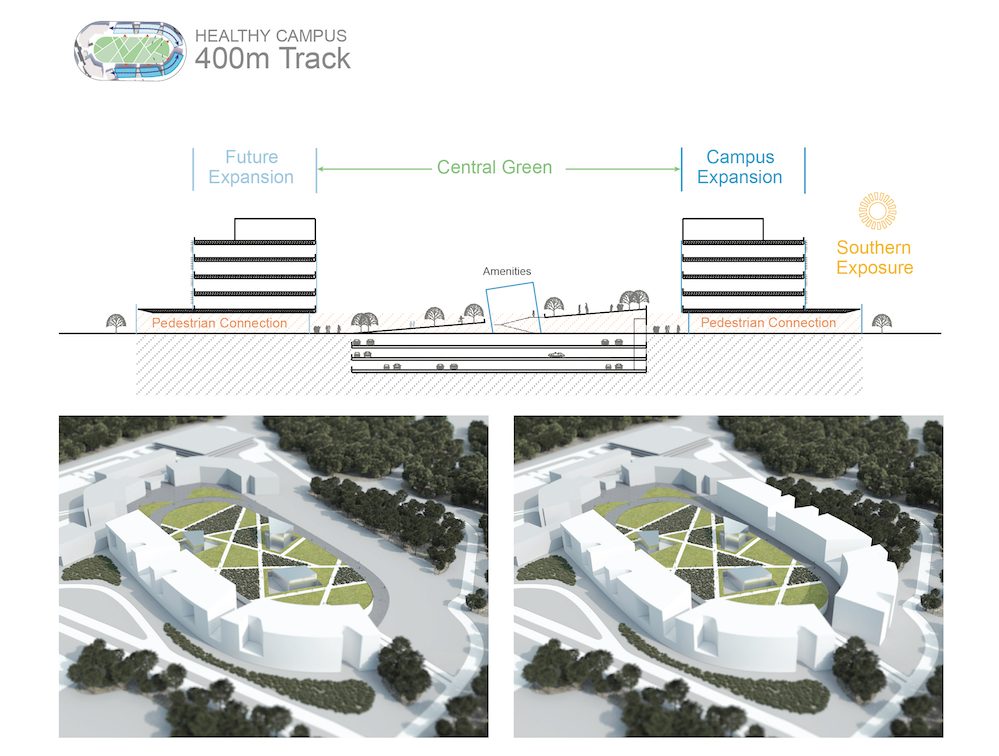

A successful corporate campus generally needs to offer four qualities: it should be accessible, it should be comfortable and have a good image, people should be able to engage in an array of activities, and it should be sociable. Other attributes that contribute to making a vibrant campus environment include a place to meet (remember, outside), a place for exchange, and a place that fosters ‘community’ pride. Great campuses also have spaces that serve as the heart of the development that typically provide a nexus of activity between two or more buildings, departments, or land uses. Ultimately, employee well-being and happiness may be bolstered by free coffee in the lounge, but the areas outside of the office deserve added attention: work stress levels are reduced when employees are able to access outdoor environments during the workday.

In practice, my firm has numerous projects that are aligned with this sentiment. One such project currently in design is for a publicly traded multinational manufacturer on a 66-acre exurban campus. Equal attention is being attuned to both campus cohesion and connectivity as to the diatribe of interior workplace settings. Alas – outside in! Their goals parallel principles of great public space and include:

- Consolidate and connect associates with an internal ‘main street’

- Activate the campus with places and spaces for people to gather

- Anchor the campus with a new center of gravity and nexus of activity

- Extend the buildings into the green and the green into buildings

- Realign lines of movement, views, and edges of outdoor space

- Intertwine the brand with new outdoor amenities

- Make pilot projects and test what works

In truth, the return to campus approach should resemble the lively students, faculty, staff, and visitors crisscrossing our great university greens. Given that these large real estate holdings have carried a big share of local tax load, elected officials should be amenable to moving away from zoning that mirrors rules for single-family homes and fully embracing the mixed uses of a planned unit development. A transformation of this nature is underway in the Township of Wayne, New Jersey where a 192-acres former corporate headquarters is giving way to plans for 1,360 residential units, retail, recreation, and contemporary offices for companies ranging from mature to startup.

The diversity of campus typologies and mix of uses means there is no one-size fits all solution.

To the extent that the ‘campus of the future’ supports work/life balance through hybrid and remote strategies, envisioning the campus of the future requires addressing experiential equity across the workforce. This may mean providing a new profile of on-campus amenities and services so the in-person workforce can achieve the same work/life balance as their counterparts. The diversity of campus typologies and mix of uses means there is no one-size fits all solution. What works to improve campus cohesion and attachment to place in one area may not be effective, feasible, or necessary in a different context. More universal is the idea that long-range campus planning must be examined in the dynamic context of the post-pandemic workplace. Program, location, landscape, services, amenities, facility utilization, and land use are all variables that must be considered as the modern workplace adapts to the needs and desires of the workforce whether in-person, hybrid, or remote.