Gary Miciunas explores the behavioral science that may help make more choice in the workplace work for you.

What do we really mean by “the freedom to choose when, where, and how to work?” This phrase has become the mantra of our discourse on the new workplace. In preparing for Work Design’s upcoming panel discussion, “Designing for Choice in the Workplace” on July 28 in Chicago, I began to think more about the distinction between “freedom” and “choice”. Does more choice suggest more freedom? Can this distinction explain why so many individuals and organizations are struggling together in trying to put this new workplace mantra of flexibility into practice?

It may be that it is not a lack of choices, but rather, a lack of freedom that is hindering workplace transformation. If this is the case, the creation of choices in terms of when, where, and how to work may not be enough. In this article, I explore how we can create a better context for choice in the workplace.

To begin with, the roles of change managers and designers need to extend into the realm of creating the context for choice, i.e., “the freedom to choose”. Such influence would involve the removal of cultural barriers that limit freedom and choices on the part of individuals and organizations. Why are individuals and organizations reluctant to adopt such flexibility in schedules, locations, and modes of working?

I mentioned these questions to my best friend, who happens to be a therapist, who told me it all boils down to hope and fear.

“Hope and fear?” I asked. “Nothing else?”

“Nope, it’s just about a mindset of either hope or fear that drives people to make choices. Sometimes they simply need help in creating a sense of calm in order to see more clearly that they are the ones holding themselves back.”

So, here I begin by exploring some fundamentals about emotion and behavior that operate at the level of both individuals and organizations. Behavioral economics and neuroscience offer us some clues.

If we are to extend our influence as designers, we need to better understand human emotions and underlying motivations that are influencing behavior.

If we are to extend our influence as designers, we need to better understand human emotions and underlying motivations that are influencing behavior. What can we learn from neuroscience about how emotions of hope and fear affect behavior? Likewise, what can we learn from behavioral economics about how the presentation of choices influences what people choose for themselves? Can such knowledge help designers to be better present options in a way that helps people make better decisions? Is there any merit in thinking about offering workplace flexibility as if “retailing” these options as products and services to employees as consumers? Are more choices better?

In a post on her blog, Leigh Stringer has previously highlighted the application of “choice architecture” to encourage healthier nutrition choices at work. These consumer behavior concepts have been applied to making better food choices, better healthcare choices and all sorts of other lifestyle decisions. In their book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein coined the terms “choice architecture” and “choice architect”:

- Choice architecture is the design of different ways in which choices can be presented to consumers and the impact of that presentation on consumer decision-making.

- A choice architect has the responsibility for organizing the context in which people make decisions.

Can we extend the ideas and tools of choice architecture and the role of choice architects to apply to freedom and choice in new ways of working? Are these concepts applicable to workstyle choices about when, where, and how to work?

The consumerization of workplace

The idea of “consumer” has entered the workplace lexicon suggesting that employees are consumers of products and services, e.g., “Consumerization of IT” and “Bring-Your-Own-Device” (BYOD) and more recently, “Consumerization of CRE”. What can we glean from the research and experience of those who study the design of choice and how consumers make decisions when presented with a range of options?

Such knowledge and insights may be very relevant to designing workplaces that present employees with choice among a variety of work settings and related services. How can we improve the adoption of these new ways of working? From a change management perspective, are we creating the right context that fosters choice in the first place? From a decision-making perspective of the employee-as-consumer, are we improving or limiting their ability to make the best choices for themselves? We need to go beyond thinking of knowledge workers as consumers, and better understand them first as people, if we are to provide a better work experience that improves well-being.

In asking these questions, we also need to consider: 1) the role of the workplace in the overall “employee experience”, and 2) the growth of “well-being” and “wellness” programs being sponsored by employers, concurrent with the rise of “mindfulness” in the workplace. Organizations are increasingly investing in employer branding — improving their reputation as an employer — by creating an organizational climate that reduces stress and anxiety and improves health and productivity. Offering employees choice in flexible work arrangements, including schedule and location options, relies upon an employer brand being known for its culture of trust and responsibility. Brand is important because it allows employees to align their emotional associations of personal values, beliefs and attitudes with those of their employer-of-choice. The closer this alignment becomes, the greater the likelihood of increasing employee engagement.

In the workplace discourse, we’ve also heard the phrase “gamification of work” as a strategy for employee engagement. As Jim Davies speculates, game designers are all too clever in knowing how to create a sense of anticipation by incorporating intermittent, random, in-game rewards that make any game a more compelling user experience. Is it possible to make the experience of work and workplace a more compelling experience through incentives and rewards?

The influence of hope and fear in decision-making

“May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.” That’s a Nelson Mandela quote, and it sums up what employers and employees may be mutually seeking from each other. Research by Deloitte suggests that leading organizations will need to balance profit and purpose in order to attract and retain new talent. Aspirational, hope-based leadership will need to replace command-and-control, fear-based management practices. Lack of purpose is a major reason why younger people leave their jobs.

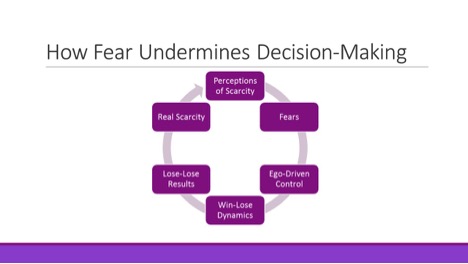

Let’s briefly explore the influence of these two mindsets of fear and hope in decision-making. In a post by Well Spirit Management Consulting, Dr. Jeff R. Hale references the work of Dan Maruska in How Great Decisions Get Made: 10 Easy Steps for Reaching Agreement on Even the Toughest Issues. Maruska’s models highlight how fear undermines decision-making and how hope stimulates great decisions.

How fear undermines decision-making

A fear-based mindset is grounded in perceptions of scarcity and limited resources. The fear of not enough resources to go around for everyone drives ego-centric attitudes, beliefs and behaviors. We see this play out in traditional office environments with the resulting allocation of space reflecting the power and status of hierarchy in the organization. A minority of people win in terms of the amount and quality of space allocated to them, while others lose in terms of lacking access to such limited resources in short supply. Individualistic, ego-driven cultures reinforce win/lose dynamics by not creating a context in which more people may gain access to privacy, daylight, and views. Such access is reserved for the privileged few. This competition for resources perpetuates a cycle of scarcity and a fear-filled place.

How hope stimulates great results

Hope is the anti-dote to fear. A hope-based mindset breaks the cycle of fear. Something better can be imagined when people share their hopes for the common good of both individuals and the organization. This leads to cooperative and collaborative behaviors and the potential for breakthrough outcomes that benefit more stakeholders. Maruska explains that letting go of our own piece of the pie creates a more satisfying pie for all. These ideas are consistent with the sharing economy in which fewer resources are required when more people share them with each other as a community. This is clearly evident when the adoption of new ways of working leads to a redistribution of office space that better serves more people, e.g., shared access to privacy, daylight, and outdoor views that improves overall health and productivity of individuals and results in bottom-line benefits to the organization.

These two mindsets are deep seated in the natural evolution of the human brain after centuries of competition and cooperation. The rise of the shared economy shows us that there’s plenty to go around when we coordinate underutilized resources, cooperate, and trust each other (Airbnb, Zipcar, etc.). Such innovative approaches based on hope and aspirations may serve as business models for the new workplace.

Maya Angelou wrote that “Hope and fear cannot occupy the same space at the same time. Invite one to stay.” This poetic advice mirrors what the executive function of our brain is constantly attempting to do in order for us to choose a best course of action. In Ask a Neuroscientist, Nick Weiler helps us understand how people behave according to a fear-based or hope-based mindset that results from a tug-of-war within our brains. Separate regions of the human brain specialize in responding to threats of fear and promises of reward while another tries to balance these opposing instinctual tendencies.

The amygdala recognizes and responds to frightening stimuli and steers you away from danger. This is where fear resides cautioning us about the risk of negative outcomes.

The nucleus accumbens is the center of the brain’s reward system. It processes stimuli that lead to the promise of rewarding experiences. This is where hope resides luring you toward joy and pleasure of positive outcomes.

The “executive” function of the brain centered in the prefrontal cortex region holds court and weighs all instinctive fears and desires. It judges all factors while facing the specific situation in determining what appears to be the best course of action. It senses both the plea of hopefulness and the plea of fearfulness and invites one to stay.

Whenever people fear repercussions of their decisions and actions, they prevent themselves from moving toward desires of rewarding experiences. Sometimes this is wise if the risk of endangerment is too great. Individuals’ perceptions of social norms in a cultural context, e.g., whether to follow convention and play it safe or to break the rules, determine risk-aversion or risk-taking. Risk aversion results whenever fear of danger dominates. Risk-taking results whenever hope of reward dominates. Workplace transformation requires risk-taking on the part of both individuals and organizations to the adopt innovative practices.

What does this all mean when it comes for designing for choice in the workplace?

Given the above ideas, if we recognize that fear and hope operate at the levels of both organizational behavior and individual behavior, then what must we as designers do in the way of designing for choice? We must expand our role to co-create with our clients the right “context” in which these choices will be offered to employees by the employer. This combination of context and choices must encompass the full spectrum of employer branding and employee experience. This experience extends beyond the walls and floors of an office building to include the work/life experience throughout a day in the life of a worker, and what it’s like to work for an organization. Does its culture emphasize autonomy and discretion in providing employees the flexibility to accomplish their collective work by making informed choices for themselves?

In another article by Stringer in this magazine’s Premium Content series — “The Power of Choice in the Workplace” — she has also pointed out the research of Karasek and Theorell on psychological demands and decision latitude in job design. Their studies conclude that by allowing workers to select their own work routine, i.e., control over their work and work environment, employees experience more positive health outcomes even under stressful conditions. This yields mutual benefits for individuals and organizations.

In response to these challenges, designing for choice must include the design of services and amenities. Complex organizations can learn a great deal from the playbooks of coworking environments and innovative serviced offices that are mastering the art of hospitality and curating community.

Further, research on self-managed working time and employee effort concludes that worker autonomy produces a moderate increase in work effort and that “both employers and employees should benefit from the use of SMWT”. Workplace transformation involves designing for choice and co-creating the right context that encourages employee latitude in flexible ways of working.

To become an employer-of-choice in the open talent economy, organizations must come to terms with offering flexibility. Those employers who can do this should be more competitive in terms of both attracting talent and controlling cost. A significant percentage of surveyed Millennials say they will choose workplace flexibility over pay. Employers face these challenges as an increasing number of workers also join the ranks of the contingent workforce by choice, opting for temporary work arrangements with flexibility outside of permanent employment positions.

In response to these challenges, designing for choice must include the design of services and amenities. Complex organizations can learn a great deal from the playbooks of coworking environments and innovative serviced offices that are mastering the art of hospitality and curating community. These alternative work environments excel at creating a place where people want to be.

In an article I wrote for Work & Place, “The Design of Work & the Work of Design”, I suggested that workplace designers will add more value than ever by applying design thinking beyond workspace design. Such a human-centered approach to workplace-as-a-service would emphasize knowledge workers’ experience of both “work” and “place.” Since then, my associates and I at NELSON are advancing this suggestion beyond service design to include the integration of information design and experience design in employer branding and employee experience. This holistic “SIX” approach merges three emerging design disciplines to unify employer branding and employee experience:

- Service Design

- Information Design

- eXperience Design

Service design conceives entire ecosystems to bring together the seamless delivery of all services that are necessary for an optimal customer experience. In the marketplace, we are inspired by such innovations in citizen-centered government services, patient-centered healthcare, and student-centered education. Why not provide the same for employee-centered workplaces?

Information design is the art and science of presenting information in a way that people can understand and apply it. This relies upon visualization and stories to reveal what data is telling us. This can be applied to location-based amenities that are available in the nearby vicinity, way-finding guides to get your there, and a myriad of other user needs for information about activity-based work settings and related services.

Experience design integrates all touchpoints and channels, products, processes, services and environments in meaningful and relevant ways that elevate the quality of the user experience. Applied to the full range of work settings, experience design has the potential to differentiate the employee experience of the workplace as an expression of the organization’s brand values, attitudes, and beliefs. In other words, from an employee perspective, how does an individual experience all aspects of the employer brand in the workplace?

Together, the intersection of these design disciplines have the potential to unify the employer brand and employee experience in the context of the workplace. Ultimately, an employer brand with the reputation of an aspirational culture is based on mutual trust and shared hopes. It is reflected in the ability of its employees’ to exercise their freedom to choose without fear among a menu of flexible options in their schedules, locations and work modes. This is what we mean by designing for choice and co-creating the freedom to choose.

[/cointent_lockedcontent]